Sold

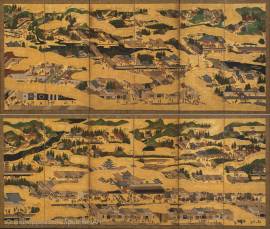

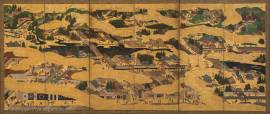

A pair of six-panel screens with views of Kyoto

Rakuchū Rakugai Zu

Views of Kyoto

Edo period, mid 17th century

Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, colors, and gold on paper

Each 121 by 282 cm

Folding screens depicting the ancient capital city of Kyoto and its surroundings (rakuchū rakugai zu) are among the most popular genres of Japanese painting. The broad surfaces of folding screens (byōbu) were ideally suited to the panoramic cityscape, as they afforded artists opportunities both to present sweeping vistas of the capital and to focus on details of everyday life in the city. Kyoto screens first appear in documents in the early sixteenth century, and upwards of two hundred known examples survive from the sixteenth and seventeenth century, when production of these works reached its peak.

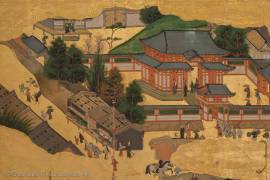

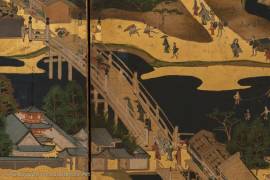

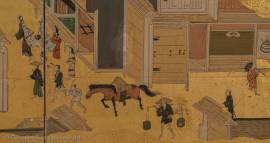

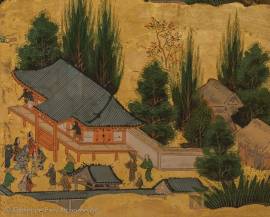

The present pair of screens can be securely dated to the mid-seventeenth century on the basis of their style and composition and the various monuments and activities depicted in the unfolding views of the city. The screens belong to a general type or sub-genre of Kyoto screens that pair views of Kyoto’s eastern hills in one screen with views of its western sections and suburbs in the other. Typically the procession of the mid-summer Gion Festival appears in the eastern, or right screen, while another procession approaching Nijō Castle appears in the western, or left screen. In the present example the grand procession of the Emperor GoMizuno’o (1596-1680) to Nijō Castle in 1626 is depicted in lavish detail, beginning with mounted imperial officials and five oxcarts in the left screen, and extending to the sixth panel of the right screen, where the emperor’s palanquin is shown about to depart from the Imperial Palace. Emperor GoMizuno’o’s visit to

Nijō Castle was such a grand event, requiring years of planning and the reconstruction of portions of the castle, that it continued to be depicted long after the event occurred.

While processions in the right and left screens provide a thematic fulcrum around which other motifs are organized, in the present pair the many famous places and pursuits of the capital’s citizens provide the most fascinating details. Two Kabuki theaters, for example, appear on the east bank of the Kamo River at Shijō; of these the southern theater, Minami-za, continues to stage performances in the same location. On the street in front of the temple Seiganji, shown just below the Kabuki theaters and slightly to the left, several priests carry a banner with an image of a bell to raise funds for their temple. Well-known landmarks such as the Great Buddha Hall (destroyed by lightning in 1798) and the long Sanjūsangendō appear in the first two panels of the right screen, but the artist devoted considerable attention also to the gate of the temple Higashi Honganji near the lower edge of the first panel. In the left screen we find landmarks such as Kitano Shrine in the first panel from right, the Golden Pavilion with an enormous phoenix ornament on its roof just above Kitano Shrine, Nijō Castle in the center, Nishi Honganji at the bottom of the sixth panel, and the temples and shrines of Arashiyama in the upper portions of the fifth and sixth panels. From their beginnings Kyoto screens always featured seasonal motifs and the present pair features blossoming cherry trees in the right screen and scarlet maple leaves in the left screen, emphasizing spring and fall, the best times of the year to visit Kyoto.

Kyoto screens were produced in large quantities in the Edo period, especially in the 17th century, when national unification and peace under the Tokugawa shoguns’ regime allowed urban economies to flourish as never before. The shogunate’s policy of “alternate attendance” (sankin kōtai) required regional warlords allegiant to the Tokugawa to divide their time between Edo, the administrative capital, and their home domains, ensuring a near-constant flow of people, products, and information throughout the realm. Many people passed through Kyoto, which retained its aura as the center of religious faith, tourism, and art production, and the city’s

visitors surely sought after Kyoto screens as luxury souvenirs of their urban adventures. That some twenty other examples of Kyoto screens, including examples in the collections of Bukkyō University, the Okayama Prefectural Museum, and the Chiba Prefectural Museum, share the same overall composition as the present screens attests to the circulation of compositional templates among a diversity of painting studios. Although the compositions are similar, individual works have their own unique details, ensuring the endless fascination with which Kyoto screens continue to captivate their viewers.

Matthew McKelway Professor of Japanese Art History, Columbia University

Sku: byo-1195

- 1 of 2

- seguente ›

Info works

Copyright © 2016 - giuseppe piva - VAT: 05104180962