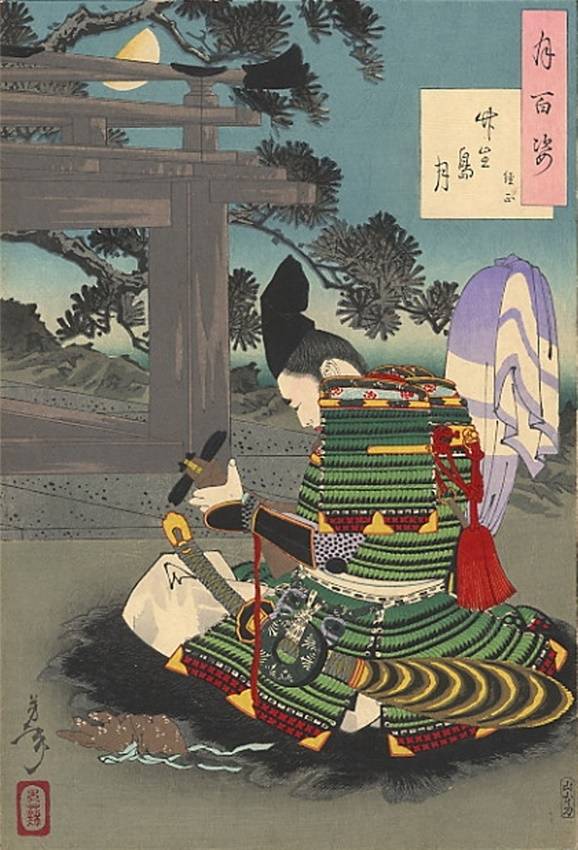

Bu and Bun: The Arts of War and Peace

In addition to great strategic and military skill, most samurai had to be skilled in the civil arts. The warrior's ideal balance of military and artistic skills is well captured in this description of daimyō Hosokawa Yusai (1534-1610):

Renowned for his elegance, he is a complete man who combines arts [bun] and weapons [bu]. A man of nobility, a descendant of Emperor Seiwa's sixth grandson, he was a ruler endowed with impressive dignity and inspiring decorum... He built a splendid castle, majestic, beautiful and tall.... He discussed Chinese poetic styles and recited by heart the secret teachings of Japanese poetry....

Although Minamoto Yoritomo, the first shogun of Japan, urged warriors not to show excessive interest in court culture, by the late 13th century literary activities-poetry composition and reading of classical Chinese and Japanese texts-were already an integral part of samurai's life. In the 17th century, military regulations even required samurai to engage in such practices. The arts of peace and war, including archery and horseback riding, were therefore to be pursued with the utmost care. The rule has always been to practice "the arts of peace with the left hand and the arts of war with the right," mastering both.

This emphasis on cultural competence stemmed from the samurai's need to rule the lands acquired through war. To rule, it was necessary to be literate, as to draft documents, samurai had to have at least a minimum of calligraphy skills and knowledge of literary conventions. Their ability to participate in court arts, such as classical Japanese verse (waka), reinforced the samurai's authority, conferring dignity and prestige on warriors who frequented aristocratic circles. Like nobles, samurai often attended social gatherings where poetry was recited, written or exchanged. Samurai children were also expected to prepare for life by studying Chinese and Japanese literature as well as Confucian texts, alongside martial skills such as archery and horseback riding. Poems were also used to recite prayers for victory in battle and to communicate with warriors from other regions.

Among other pastimes, high-ranking samurai were often avid lovers of painting. Warrior patronage of painters and craftsmen advanced the visual arts throughout the period of military rule, and daimyō competed to fill their mansions and castles with brightly colored screens and beautifully decorated objects for daily use. In addition to objects imported from China or paintings inspired by Chinese painting styles, favorites were screens painted with naturalistic scenes or with subjects more related to the warrior world such as falconry, horse racing and dog hunting.

Nō theater, a traditional form of drama, was another cultural activity valued by the samurai. Often drawn from classical literary sources, Nō plays emphasize Buddhist themes and focus on the emotions of a main character tormented by love, anger or grief. The commander Toyotomi Hideyoshi studied and acted in Nō plays himself, including during military campaigns. Nō was taken so seriously that during the Edo period (1615-1868), every daimyō family had a complete set of clothes, masks and musical instruments for performing such plays.

Finally, many samurai were devoted to the "Way of Tea" (Chado, also known as Chanoyu, lit. "hot water for tea"). In its simplest form, tea is a gathering during which water is heated, tea is prepared and served, and conversation takes place between the host and guests. Initially, samurai practiced elaborate forms of tea ceremony, sometimes involving numerous gatherings that included other social activities. Hideyoshi and Nobunaga, two of Japan's most powerful warlords, were both fervent collectors of tea utensils, made in a simple and essential taste that still has enthusiasts and collectors around the world.

Copyright © 2016 - giuseppe piva - VAT: 05104180962