The "ie" system: a different approach to signatures in Japanese art

When we handle a signed Japanese work of art we tend to illude ourselves that it has been made by a single person, the artist himself. This can certainly be true for some kind of items, like paintings and calligraphy, but when a lot of work is required, such as forging, hammering or lacquering, it is more likely that we are looking at a collective production rather than a one-man artifact.

When we handle a signed Japanese work of art we tend to illude ourselves that it has been made by a single person, the artist himself. This can certainly be true for some kind of items, like paintings and calligraphy, but when a lot of work is required, such as forging, hammering or lacquering, it is more likely that we are looking at a collective production rather than a one-man artifact.

This is certainly true also for European art, where an important artist had their workshop helping them on repetitive or heavy tasks, but in Japan, this goes a little farther, due to a system called “ie”. The ie system, which means “family”, has ancient roots and was very much pushed by the military government during the Edo period; still, nowadays it is quite well diffused for small family business. The logic of this business/family system can be described in the following points:

- The primary objective is to survive and prosper: as the ie prospers so does the family

- The members will sacrifice their own personal benefits for the benefit of the ie

- The head of the ie has unconditional power over the rest of the family

- The successor to the head of the ie is likely to be his first-born son

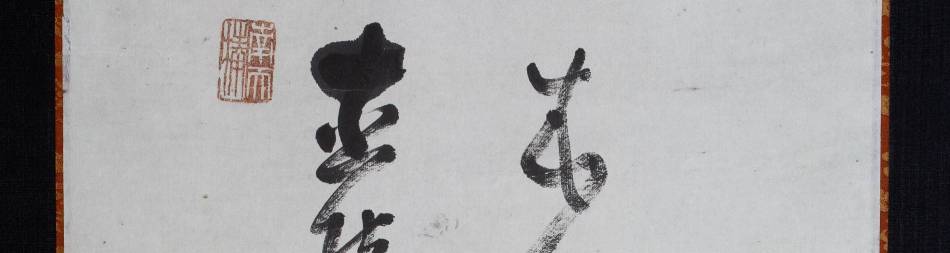

It is then clear that in this system family and business are the same thing and that the only person who really matters is the ie’s head, the “master”. So what happens when a workshop formed by an entire family produces something? Easy to guess: everything is labeled as “made by the master” himself. This common practice has two different names, depending on who actually wrote the signature: “daisaku”, when a student/son produces a work of art and the master put his signature, or “daimei”, when even the signature, with the master’s name, is written by somebody else.

The ie system also required than when a good student was going to become the new master but he was not part of the family, he needed to be adopted in order to succeed: there are plenty of examples where an artist had no sons and his successor had been adopted and became both heads of the business and of the family where he moved in!

We need to say immediately that daisaku/daimei signatures are considered fully authentic when considering Japanese works of art, as the style and the quality of a workshop’s production was supervised by the master and in most cases, anyway, it is not possible to distinguish the actual maker.

This system is also the reason why we often find very good works of art signed by completely unknown makers. We immediately react asking how is it possible that there are no other signed works by such artists; well, the answer is that probably they had always been worked in the workshop under the ie system and never became masters of their family.

Another interesting practice that comes from the ie system and that we must face when dealing with signatures is what Japanese called shumei, which is the act of taking a father's name by the eldest son, in order to keep a sort of “trademark” on his production. The name handed down from father to son is called tsumyo and there are signed works of art where the same identical signature can indicate two or three generations of makers.

Oh, and for those who think these kind of practice are ancient, here you are some Japanese companies who used adoption for business purpose: Kikkoman, Canon, Suzuki, Toyota.

Copyright © 2016 - giuseppe piva - VAT: 05104180962